9 Basic map functions

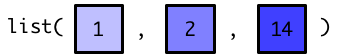

library(tidyverse)9.1 Iteration as an assembly line

You’ll often need to apply the same function to each element of a list or atomic vector. As an example, take moons, a list of vectors.

moons <-

list(

earth = 1737.1,

mars = c(11.3, 6.2),

neptune =

c(60.4, 81.4, 156, 174.8, 194, 34.8, 420, 2705.2, 340, 62, 44, 42, 40, 60)

)(This data is from the Wikipedia pages on Earth’s Moon, Mars’s moons, and Neptune’s moons).

Each vector in moons represents a planet. The elements of each vector represent the radii of that planet’s moons, in kilometers. (Note that some moons are irregularly shaped, so these are average radii.)

Say we want to figure out the number of moons that belong to each planet by taking the length of each vector. We can’t just apply length() to moons.

length(moons)

#> [1] 3length(moons) returns the number of planets in moons. Instead, we need to apply length() to each vector in moons. We could find the length of each vector by individually pulling out each one and then applying length().

length(moons$earth)

#> [1] 1

length(moons$mars)

#> [1] 2

length(moons$neptune)

#> [1] 14This strategy is tedious and repetitive, and would be even more tedious and repetitive if moons contained more planets. Fortunately, we can use functions from the purrr package to iterate through vectors and do the same thing to each element. In this reading, you’ll learn about the most basic purrr functions: the map functions.

Take a look at the purrr cheatsheet for an overview of all the purrr functions.

The map functions are like an assembly line in a factory. One conveyor belt, the input belt, transports various objects to a worker. The worker picks up each object and does something with it, but, importantly, never changes the object itself. For example, she might make a mold of the object, or grab a piece of plastic corresponding to the color of the object. Then, she places her new creation (the mold, piece of plastic, etc.) on the output belt. She does this until there are no new objects to process on the input belt and the conveyor belt stops. The factory then ends up with the same number of output objects as came in on the input belt.

Imagine the map functions as this factory. You supply the map function with a list or vector (the objects on the input conveyor belt) and a function (what the worker does with each object). Then, the map function makes the conveyor belts run, applying the function to each element in the original vector to create a new vector of the same length, while never changing the original.

In our moons example, the elements on the input belt are the vectors of moon radii. We want the worker to take the length of each vector by applying length(), producing three numbers on the output belt, each indicating a number of moons. In the next section, we’ll show you exactly how to carry out this operation with the map functions.

9.2 The map functions

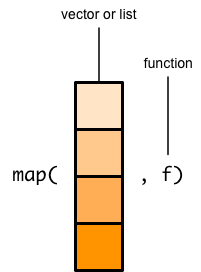

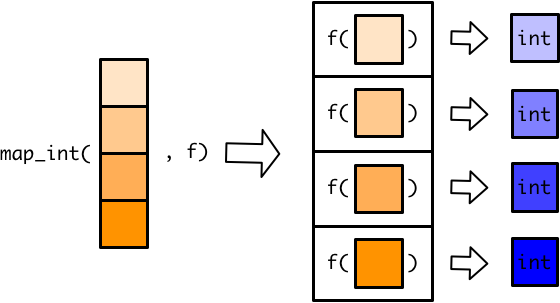

We’ll explain the most general map function, map(), first. map(), like all the map functions, takes a list/vector and a function as arguments.

(All diagrams were adapted from https://adv-r.hadley.nz/functionals.html.)

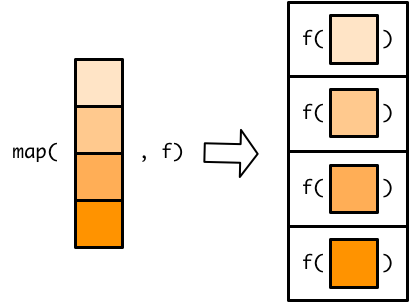

map() then applies that function to each element of the input list/vector.

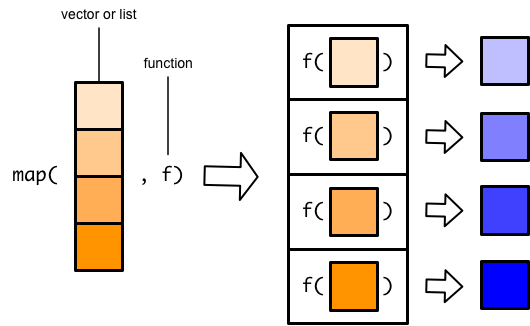

Applying the function to each element of the input list/vector results in one output element for each input element.

map() then combines all these output elements into a list.

In the assembly line metaphor, the input list/vector is the container for the items that go on the conveyor belt. The function specifies what the worker should do with each item. The items on the output conveyor belt make up the list that map() returns once it’s done.

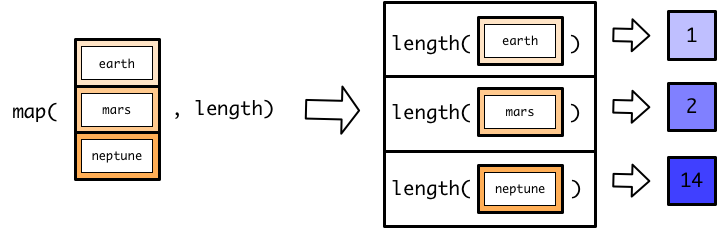

In our example, moons is our input. We want to apply length() to each element of moons, so length is the function.

Each call to length() produces an integer, so the result is a list of integers.

Here’s what the call to map() looks like:

map(moons, length)

#> $earth

#> [1] 1

#>

#> $mars

#> [1] 2

#>

#> $neptune

#> [1] 14Note that we used length, not length(), to specify which function to use. length() calls the function, while length refers to the function object.

As we already said, map() returns a list.

typeof(map(moons, length))

#> [1] "list"A list of integers is fine, but you’ll often rather have an atomic vector of integers. purrr also contains variants of map() that produce atomic vectors. There is one variant for each type of atomic vector.

map_int()creates an integer vector.map_dbl()creates a double vector.map_chr()creates a character vector.map_lgl()creates a logical vector.

length() returns integers, so we’ll use map_int() to create an integer vector instead of a list.

map_int(moons, length)

#> earth mars neptune

#> 1 2 14The result looks similar to the result we got from map(), but is now an integer vector.

typeof(map_int(moons, length))

#> [1] "integer"map_int() requires that each output element be an integer.

If each element is an integer, map_int() can then combine all the elements into a single atomic vector.

The other variants of map() that produce double, character, and logical vectors work in the same way.

We could use map() and median() to find the median moon radius for each planet.

map(moons, median)

#> $earth

#> [1] 1737

#>

#> $mars

#> [1] 8.75

#>

#> $neptune

#> [1] 71.7Or, we could use map_dbl() to produce a vector of doubles.

map_dbl(moons, median)

#> earth mars neptune

#> 1737.10 8.75 71.70Mars has very small moons!

Use map_chr() to create a character vector when using a function that produces characters, and map_lgl() to create logical vectors.

map_lgl(moons, is.double)

#> earth mars neptune

#> TRUE TRUE TRUEThe map variants that produce atomic vectors will throw an error if your function doesn’t output the correct type.

map_int(moons, median)

#> Error: Can't coerce element 1 from a double to a integermedian() returns doubles, but map_int() expects integers, and cannot coerce doubles into integers. If you get a “Can’t coerce” error when working with map functions, you’re likely using the wrong variant.

Some functions return vectors. For example, sort() returns a sorted version of a vector.

sort(moons$neptune)

#> [1] 34.8 40.0 42.0 44.0 60.0 60.4 62.0 81.4 156.0 174.8

#> [11] 194.0 340.0 420.0 2705.2Even though sort() returns a vector of doubles, we can’t use map_dbl() to apply sort() to each element of moons.

map_dbl(moons, sort)

#> Error: Result 2 must be a single double, not a double vector of length 2map_dbl() requires that the function return a single double for each element of moons because atomic vectors can’t contain other vectors. sort() returns a vector of doubles for each element, so map_dbl() fails.

Instead, we have to use map() to combine the individual output vectors into a list.

map(moons, sort)

#> $earth

#> [1] 1737

#>

#> $mars

#> [1] 6.2 11.3

#>

#> $neptune

#> [1] 34.8 40.0 42.0 44.0 60.0 60.4 62.0 81.4 156.0 174.8

#> [11] 194.0 340.0 420.0 2705.2Because map() creates lists, it’s very flexible. We just used map() to create a list of vectors, but you can also use map() to create lists of lists, lists of lists of lists, lists of tibbles, lists of functions, etc.

9.2.1 Extra arguments

In the previous section, we used sort() to arrange each vector. By default, sort() arranges in increasing order.

map(moons, sort)

#> $earth

#> [1] 1737

#>

#> $mars

#> [1] 6.2 11.3

#>

#> $neptune

#> [1] 34.8 40.0 42.0 44.0 60.0 60.4 62.0 81.4 156.0 174.8

#> [11] 194.0 340.0 420.0 2705.2To sort in decreasing order, we have to specify decreasing = TRUE inside of sort(). Outside of a map function, we would just put decreasing = TRUE into the function call.

sort(moons$neptune, decreasing = TRUE)

#> [1] 2705.2 420.0 340.0 194.0 174.8 156.0 81.4 62.0 60.4 60.0

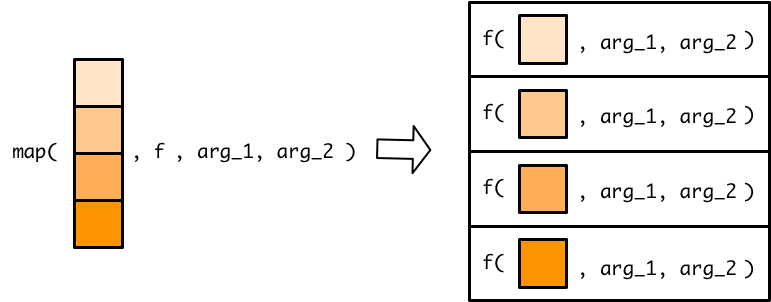

#> [11] 44.0 42.0 40.0 34.8Inside a map function, you put function arguments directly after the function name.

map(moons, sort, decreasing = TRUE)

#> $earth

#> [1] 1737

#>

#> $mars

#> [1] 11.3 6.2

#>

#> $neptune

#> [1] 2705.2 420.0 340.0 194.0 174.8 156.0 81.4 62.0 60.4 60.0

#> [11] 44.0 42.0 40.0 34.8You can add as many arguments as you like, and map() will automatically supply them to the function.

For example, the following code uses two additional arguments to find the 95th quantile for each planet, excluding missing values.

moons %>%

map_dbl(quantile, probs = 0.95, na.rm = TRUE)

#> earth mars neptune

#> 1737 11 12209.2.2 Anonymous functions

So far in the reading, we’ve only given map named functions. Recall that named functions have a name which you can use to call the function.

Say we want to convert the moon radii from kilometers to miles. Here’s a named function that turns kilometers into miles.

km_to_miles <- function(x) {

x * 0.62

}Anytime we want to convert kilometers to miles, we can now call km_to_miles().

km_to_miles(22)

#> [1] 13.6Now, we can use km_to_miles() and map() to convert all moon radii to miles. We have to use map() because km_to_miles() will return a vector for each planet.

map(moons, km_to_miles)

#> $earth

#> [1] 1077

#>

#> $mars

#> [1] 7.01 3.84

#>

#> $neptune

#> [1] 37.4 50.5 96.7 108.4 120.3 21.6 260.4 1677.2 210.8 38.4

#> [11] 27.3 26.0 24.8 37.2If we’re not going to use km_to_miles() again, we don’t need to make a named function. It will be less work and more succinct to just create an anonymous function inside map(). Recall that anonymous functions are just functions without names, and the full syntax looks like this:

function(x) x * 0.62

#> function(x) x * 0.62We can copy this anonymous function directly into map().

map(moons, function(x) x * 0.62)

#> $earth

#> [1] 1077

#>

#> $mars

#> [1] 7.01 3.84

#>

#> $neptune

#> [1] 37.4 50.5 96.7 108.4 120.3 21.6 260.4 1677.2 210.8 38.4

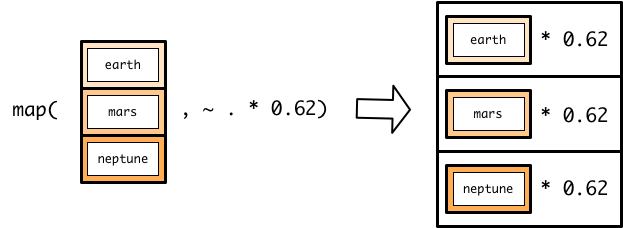

#> [11] 27.3 26.0 24.8 37.2The full syntax for anonymous functions is clunky, so purrr provides a shortcut. Here’s what the code looks like if we use the shortcut:

moons %>%

map(~ . * 0.62)

#> $earth

#> [1] 1077

#>

#> $mars

#> [1] 7.01 3.84

#>

#> $neptune

#> [1] 37.4 50.5 96.7 108.4 120.3 21.6 260.4 1677.2 210.8 38.4

#> [11] 27.3 26.0 24.8 37.2The ~ tells map() that an anonymous function is coming. The . refers to the function argument, taking the place of x from the full anonymous function syntax.

Just like when you supply map() with a named function, map() will apply an anonymous function to each element of moons. You can think of . as a placeholder, referring to earth, then mars, and then neptune as the conveyor belt delivers the vector of each planet’s moons to the worker.

If a named function does not exist for your mapping, we recommend using an anonymous function instead of creating a named function, unless you’ll use the function again or the function is very long. We also recommend always using the syntax shortcut instead of the full anonymous function syntax.

Anonymous functions can be confusing and tricky to get right. If you’re struggling to get the syntax correct, try testing your anonymous function on just a single element of your list. Here, we’ll explain one strategy for doing so.

First, assign a single element of your list to the variable .. This looks strange, but means you’ll end up with a function that uses the purrr anonymous function syntax.

. <- moons[[3]]

.

#> [1] 60.4 81.4 156.0 174.8 194.0 34.8 420.0 2705.2 340.0 62.0

#> [11] 44.0 42.0 40.0 60.0(We picked the third element because Neptune is more interesting than Earth, but it’s usually easiest to simply pick the first element with [[1]].)

Then, figure out how to perform your desired operation on just that element. Check that the output is correct.

. * 0.62

#> [1] 37.4 50.5 96.7 108.4 120.3 21.6 260.4 1677.2 210.8 38.4

#> [11] 27.3 26.0 24.8 37.2Now, copy and paste your code into map(). Just remember to put a ~ at the beginning.

moons %>%

map(~ . * 0.62)

#> $earth

#> [1] 1077

#>

#> $mars

#> [1] 7.01 3.84

#>

#> $neptune

#> [1] 37.4 50.5 96.7 108.4 120.3 21.6 260.4 1677.2 210.8 38.4

#> [11] 27.3 26.0 24.8 37.2Let’s walk through a more complicated example. Say you want to find the number of large moons that belong to each planet. We’ll define a large moon as a moon with a radius greater than 100 kilometers.

First, assign an element of your list to ..

. <- moons[[3]]

.

#> [1] 60.4 81.4 156.0 174.8 194.0 34.8 420.0 2705.2 340.0 62.0

#> [11] 44.0 42.0 40.0 60.0Then, build and test your function just for ..

First, we need to subset . so that it just includes moon radii greater than 100. Recall the syntax for subsetting vectors. x[x == 1] extracts just the elements of some vector x that are equal to 1. x[x > 2] gives you all the elements of x greater than 2. Use this syntax to extract the moon radii in . that are greater than 100.

.[. > 100]

#> [1] 156 175 194 420 2705 340Then, take the length of this new vector to find the number of moons it contains.

length(.[. > 100])

#> [1] 6Now, copy and paste your code into a map function after a ~. We’ll use map_int() because length() returns integers.

moons %>%

map_int(~ length(.[. > 100]))

#> earth mars neptune

#> 1 0 6This strategy makes the purrr anonymous function syntax less abstract and allows you to test your anonymous functions before plugging them into a map function.

9.2.3 Tibbles

All the examples so far have used the map function on moons, a list of vectors, but the map functions work on any type of vector or list, including tibbles.

Tibbles are lists of vectors. Notice that when you create a tibble with tibble(), you create a vector for each column.

y <-

tibble(

col_1 = c(1, 2, 3),

col_2 = c(100, 200, 300),

col_3 = c(0.1, 0.2, 0.3)

)Because the elements of a tibble are the vector columns, map functions act on the tibble columns, not the tibble rows.

map_dbl(y, median)

#> col_1 col_2 col_3

#> 2.0 200.0 0.2Here’s another example that finds the number of NA’s in each column of nycflights13::flights.

nycflights13::flights %>%

map_int(~ sum(is.na(.)))

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time

#> 0 0 0 8255 0

#> dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time arr_delay carrier

#> 8255 8713 0 9430 0

#> flight tailnum origin dest air_time

#> 0 2512 0 0 9430

#> distance hour minute time_hour

#> 0 0 0 0